what living is about: low-income kids of color in a white world

Posted: August 18, 2014 Filed under: art, creative process, education, empathy, equality, issues, protest, race/ethnicity, violence | Tags: AmeriCorps, black bodies, black boys, economic justice, Ferguson, Michael Brown, Philadelphia, poverty and creativity, racial justice, shooting of unarmed black boy, volunteering, working with kids Leave a commentFresh out of college, I moved to Philadelphia and joined AmeriCorps. It was easily one of the best things I’ve ever done in my life.

I found myself–a young, middle-class, white woman–walking through the toughest neighborhoods of Philly on my way to improve literacy rates among kids. It was daunting. I imagined all sorts of crazy scenarios, but I quickly learned that no one cared about me. No one was going to bother the white girl in her pickup truck, and the schools all had strict security protocols. Funny where your imagination can take you if you let fear guide it, but recognizing that fear and where it comes from makes all the difference.

Every day for the first couple of months, however, I came home feeling sick. The kids I worked with lived in terrible circumstances, and while I got up close and personal with their daily struggles, I got to walk away from them every day. I got to return to my quaint brick building and eat sundried-tomato hummus from my local co-op.

I wasn’t used to being around extreme poverty, and it made me ache. One of the elementary schools I visited regularly was surrounded on three sides by projects and the fourth side by derelict buildings full of squatters, as evidenced by sheets that hung in random windows. There was a high fence all the way around the building, and inside that fence, at one end, was a small playground that was nothing but blacktop.

One sunny afternoon a boy cried when he learned that it wasn’t his turn to work with me. He had told me the previous week that he watched his mother die of an overdose. He was eight. He was black. He had the sweetest heart you can imagine, but just a few years later you’d probably see him as a thug. Because that’s what happens to black boys. They hit puberty, and we decide they’re dangerous. That may as well be the end of their lives.

At Benjamin Franklin High School, the ninth-grade class I worked with read on a third-grade level, yet they all had passing grades. They weren’t being taught; they were being kept off the streets. There were three pregnant girls. One of the boys who’d done the impregnating strutted around the room while the books provided for them sat in plastic baskets in the back, books about Arthur the aardvark, little boys learning how to play baseball, and monsters eating homework.

When we worked on a project that required us to walk around the neighborhood, drug deals went down right in front of them and they didn’t bat an eye. Maybe they were busy thinking about what Arthur the aardvark might be up to.

Every Monday I spent the afternoon with a group of middle-school and high-school Latinas at a Catholic community center. It was my favorite part of the week despite always needing to go out and move my truck closer to the building before it got dark because a car down the block had been set on fire with a person in it a month before I started. One evening when I went out to move my truck, someone was stealing the car in front of mine. I just pretended I hadn’t seen anything.

The girls were lively and fun and full of ideas, but they were also full of the most heartbreaking stories. One girl told me that her uncle had molested her since she was eleven. I had this idea that two super-smart sisters could do well in school and get out of there, but then I learned that they had no concept of getting out of there. They’d never left their neighborhood. Their mom was an addict who lived and worked on the street, and they lived with their dad and his girlfriend, who was always threatening to kick them out. The older one, in eighth grade, lost her boyfriend when he was shot in the head because he had the best corner.

All of the girls wanted to be Jennifer Lopez, but other than that, they had no thought of moving beyond their neighborhood. It was what they knew. So I tried to nurture their inner JLo. I helped them write about their lives, taught them about acting, and choreographed a dance performance. Every Monday they got a little break from their daily struggle to survive; they got to laugh and sing and dance, which is what living is about.

That was fifteen years ago, and I have no idea what happened to any of those kids. I don’t know who made it, who’s dead, who’s in prison.

I think about them a lot, especially when yet another unarmed black teenager is shot by the police.

I probably didn’t do very much for those kids in the long term, but they did a lot for me. They showed me the reality of poverty and racism. They showed me how the justice system didn’t (and still doesn’t) work in communities of color, how authorities and the media have let down communities of color over and over again. Sometimes I knew about violence that didn’t make the news for some reason. Sometimes it made the news in a way that was utterly different from the story I’d heard from people who were there.

I will never stop fighting for racial and economic justice because I know the lives of kids depend on it. But sometimes it’s difficult to know what to do, especially if you’re white and middle class.

If there are demonstrations in your city, go to them. Connect with the people there to work on real change for the future.

If you work with low-income kids, find ways to nurture their creativity, which can give them solace from the difficulties in their lives and effective ways to work through those difficulties.

If you lead camps or workshops for kids, find ways to make them accessible to low-income kids. Make sure your group is diverse in terms of economic background and race/ethnicity. Get white kids accustomed to diverse environments so they question situations where everyone is white.

If you’ve got some time to volunteer, find an organization or collective that works with kids in low-income areas. Read with kids. Let them sing and dance and paint.

But don’t go in thinking you can save them. They don’t need to be saved, especially by a white person. Think of it as skill sharing or knowledge sharing. You’re going to share what you know with them, and, in turn, you’re going to learn a hell of a lot about the rest of the world.

And then share what you’ve learned with other people. Apply it to your work. Use it to change systems that have long been mired in racism and aren’t doing anyone any good. Use it to increase diversity among decision-makers. Don’t let kids get out of third grade without meeting appropriate reading levels. Question why law enforcement is mostly white in a mostly black city and the effect that has on both police and those being policed. Use strategic creative action.

When I look at pictures of Michael Brown, the young man shot in Ferguson, Missouri, on August 9, I see that eight-year-old boy crying because I don’t have time for him that day. What do you see? Don’t let fear drive your creativity and overrule your empathy. Look beyond the characteristics you have been taught to fear. Imagine that little boy and how different his life could have been.

Here are some other steps white people can take to prevent another Ferguson and work for racial and economic justice.

feminist film: “i don’t remember ever feeling this awake”

Posted: July 28, 2014 Filed under: equality, feminisms, film, gender roles, race/ethnicity, sexuality, the body Leave a commentSaid Thelma to Louise in a film that still stands as the seminal feminist big-screen journey. Because movies featuring or made by women still get far less investment than they should.

USC’s Media, Diversity, & Social Change Initiative released a study on more than 25,000 speaking characters in 600 of the highest-grossing films of the past seven years, and, unsurprisingly, the results for women are dismal. While women made some headway in comedies with a whopping third of characters, they represented less than a quarter of action-adventure roles. The number of women directors dropped, and women characters were sexualized three times as often as men. (There are even financial reasons why this should be otherwise.)

Add to that, the vast number of movies that perpetuate gender norms and contribute to rape culture, and we’ve got a pretty sorry picture.

But there are films out there that challenge traditional ideas of women, give women voices and agency, and explore women’s experiences. We can argue all day about what definition to use to categorize a movie as feminist and you’ll be disappointed if you’re favorites were left off of this list, but I’m really digging Flavorwire’s “50 Essential Feminist Films” and am ashamed to say that I’ve only seen fourteen of them. Now you know what’s on my Netflix queue.

To give you an idea of what’s on the list, here’s what I’ve seen: Meshes of the Afternoon, All About My Mother, Daisies (a feminist, anti-capitalist frolic; you too will long to stomp around in cake at a wealthy shindig), Orlando (my introduction to the incomparable Tilda Swinton), Alien, Wendy and Lucy, Female Trouble, Morvern Callar, I Shot Andy Warhol, Ladies and Gentlemen the Fabulous Stains (a young, punk Diane Lane!), Nine to Five, Clueless (yes!), A View to a Kill (an unexpected pick, but Barbara Broccoli produced and Grace Jones kicked ass), and The Punk Singer (which I wrote about recently).

This is truly an excellent list: science fiction, transgender stories, female magistrates in Cameroon, women in Tehran, Cuban revolutionaries, Maggie Cheung, Catherine Deneuve, Pam Grier and bell hooks in the same film, Margarite Duras, Margarethe von Trotta, Jane Campion, Agnès Varda. Cassavetes, our best frenemy, makes an appearance. And Julie Dash’s Daughters of the Dust, which I’ve wanted to watch ever since I read about it in college.

There are also great suggestions in the comment section. So is your favorite missing? What else would you recommend?

As for the future of film, and feminist film especially, check out these fine organizations and projects: Black Feminist Film School, Athena Film Festival, Women in Film, Women Make Movies, Reel Grrls, PODER!, and, of course, from Thelma herself, the Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media.

malala day: give a kid a book already

Posted: July 14, 2014 Filed under: art, education, feminisms, fiction, healing, issues, literature, music, protest, race/ethnicity, violence | Tags: Alice Walker, bikini kill, books, education, girls, kathleen hanna, Malala Day, Malala Yousafzai, mix CDs, mix tapes, Rebel Girl, Sylvia Plath, The Bell Jar, The Color Purple, youth 1 CommentToday is Malala Day, the birthday celebration of Malala Yousafzai, the girl the Taliban shot in the head because she wanted to go to school. That was two years ago, and I am still moved by everything she does. It’s so easy to let life unravel in the face of horrible circumstances, and yet she kept going, keeps going. Her continued existence would have been enough to fight back. Going back to school would have been enough. But Malala skyrocketed, becoming an advocate for girls’ education and a role model for girls all over the world.

Her brave yet peaceful response to the Taliban, and to all who try to hold girls back, is a great lesson for our warmongering leaders, if they took the time to really listen to girls. She doesn’t fight violence with violence; she fights it with education and, more precisely, books. Check out this new video where she explains how books are stronger than bullets.

Malala just turned seventeen. My niece is going on fourteen, and the night before she came to visit us last week my partner and I watched The Punk Singer, the movie about Kathleen Hanna. It got me all fired up about making a mix CD for my niece. (Side note: since the 80s and 90s are back in, will kids start making mix tapes again? Pretty please?) My partner and I started talking about how so much of our values and world views came from the books we found at the library or borrowed from friends, the records we collected from thrift stores and out-of-the way shops, and the zines we traded when we were kids.

My feminist life, for instance, started when I cracked open The Bell Jar and discovered that someone had put my feelings into words. The Color Purple started me on the path to racial and economic justice. When I listened to “Rebel Girl,” Kathleen Hanna was the queen of my world. I devoured these books and records and then I learned about the women behind them, and I finally had an image of the kind of woman I wanted to be.

I wanted to create, to agitate, to express myself. Each book or record was like a window to what could be.

By the end of my niece’s visit, we walked out of a used bookstore, arms piled high with books and CDs. Malala had to face gunmen to get to books; we only had to stroll into a shop the size of a warehouse and take our pick.

Though we in the US are lucky to have access to free public schools, there are a lot of arguments about the state of education here today. Teachers have their hands tied by nonsensical standardized tests that leave children of color further and further behind. To make matters worse, attendance and performance here are affected by everything from street violence and school attacks to dating violence and bullying.

But there is one way we can help young people get at least a little of the education they need. For Malala Day, think about the things that helped you find your way when you were younger, that helped to define who you are today–a book, record, print, poem–and give a copy to a kid.

Books are #strongerthan bullets.

native americans aren’t your mascots

Posted: April 14, 2014 Filed under: art, education, equality, fiction, film, issues, literature, performance art, poetry, race/ethnicity | Tags: blood quantum, Crazy Brave, James Luna, Jezebel, Joy Harjo, Louise Erdrich, Matika Wilbur, Native American, Native American art, Neil Diamond, Project 562, red face, Reel Injun, The Artifact Piece, The Cherokee Word for Water, The Round House, Wilma Mankiller Leave a commentI was reading a rather yawn-inducing piece on Jezebel describing the concept of a “basic bitch” and my eyes wandered into the comment section, which is typically fine on that site because most readers are feminist, anti-racist, etc. But I saw something really bizarre happen. A commenter who introduced herself as a Native American woman said she was tired of all the anti-white articles and comments popping up all over the internet, and people responded by challenging her Nativeness, even going so far as to demand to know what tribe she belongs to, whose rolls she’s on, what rez she lives on.

They were doing this because they felt like she was complaining about reverse racism (which pretty much only happens at an individual level and not at a systemic level, so it’s not the same thing as actual racism, which is pervasive and affects every aspect of people’s lives), a reaction they thought was kind of racist in and of itself, so they responded with…their own racism.

Let’s just get this out of the way: it’s not really okay to question how Native someone is just because you don’t think they act or look like a Native person should. Because of the problem of blood quantum, people still think it’s perfectly acceptable to single out Native Americans as the one group that must prove their ethnicity. With blood.

Blood quantum is the measure of how much Native blood a person has. It’s like the one-drop rule, but instead of being used to classify as many people as possible as non-white so they could be segregated from white people and treated like second-class citizens, blood quantum was established by the US government (and back in the colonies) to actually limit the number of Native Americans. The smaller the tribe, the less the government had to offer in a treaty. Even now, government benefits to tribes are measly due to blood quantum. Lived all your life on the res, 100% Native, but descended from several different tribes? Too bad, you don’t have enough blood from this one tribe to be a full member, so the US government ignores you. Old tribal census rolls are incomplete because the US government forced your family off their land, sent their kids to boarding schools where their language was beaten out of them, and your grandfather was delivered in a shack with a dirt floor (by a drunk doctor who screwed up his birth certificate) to parents whose records don’t appear to exist? Sorry, friend, you’re out of luck.

Last week I saw this image of a white Cleveland baseball fan in red face haughtily explaining himself to a Native man. In the middle of the city. At a public event. In red face. Like it’s totally cool.

It’s an understatement to say that Native Americans are only visible in our society as mascots. And even then those mascot roles are often played by white people (see Johnny Depp as Tonto in The Lone Ranger and Rooney Mara’s recent casting as Tiger Lily in an upcoming Peter Pan movie). If you want to see Native people represented as real, multi-dimensional human beings, you have to dig around.

To help you get started, here are a few creative projects that challenge the stereotypes that even some “anti-racist” Jezebel readers perpetuate.

- The Cherokee Word for Water: This recently released film about Wilma Mankiller, the first woman chief of the Cherokee Nation, focuses on her big impact on a tribal community without water.

- Reel Injun: Filmmaker Neil Diamond won a Peabody Award for his exploration of Hollywood’s portrayal of North American Natives.

- Project 562: Matika Wilbur has been photographing people from every federally recognized tribe in the US for this Kickstarter-funded project. She includes this anecdote on her Kickstarter page: “I had this incredible experience at the bottom of The Grand Canyon. The elders appointed a teenage boy to help me carry my equipment to photo shoots (since there aren’t cars down there, and I’m clumsy on a horse). He was kind of quiet at first, standoffish even. But after the first interview and photoshoot, he was excited for the next one. He started suggesting ideas. I could see him listening as we spoke to his elders. That evening, he revealed that he had walked a despairing path, having struggled with depression and his own sense of Tribal identity. As I was leaving, he shyly pulled me aside, and told me that this project gave him a new sense of hope. He said that he believed in me. He said that I was the first lady that he’d ever met that had went on to ‘do something’. He thanked me for giving him hope. He said that his experience with Project 562 had meant more to him than he could articulate.”

- The Artifact Piece: Clad in a loincloth, performance artist James Luna lies in a display case to underscore the problem of presenting Native people as artifacts of the past instead of living, evolving people of the present.

- The Round House: Louise Erdrich’s latest novel of an Ojibwe family won the 2012 National Book Award.

- Crazy Brave: Poet Joy Harjo’s new memoir chronicles her search for her voice and herself. What she’s learned about the debris of trauma: “You can use those materials to build a bridge over that which would destroy you.”

for further exploration: music, art, film, and creative solutions

Posted: February 3, 2014 Filed under: art, creative process, education, empathy, equality, feminisms, film, for further exploration, gender roles, music, performance art, protest, race/ethnicity, sexuality, the body, violence, visual art | Tags: Allison Wolfe, Antoine Tempe, art and Islam, creativity in development, creativity in rural life, cultivating empathy, Dakar, Global Lives Project, Ibi Ibrahim, Jemilah King, Lindsay Bottos, Maria Alyokhina, Masha Gessen, Nadezhda Tolokonnikova, Omar Victor Diop, online harassment, ONOMOllywood, Pussy Riot, racial inequality in film, riot grrrl, zines Leave a commentThe latest on Pussy Riot: Formerly imprisoned members Nadezhda Tolokonnikova and Maria Alyokhina are coming to New York to talk about political prisoners for an Amnesty International event. Despite Putin’s attempts to silence them, Tolokonnikova and Alekhina remain unwavering in their commitment to social change. Journalist Masha Gessen’s recently published book Words Will Break Cement: The Passion of Pussy Riot is at the top of my must-read list.

More riot grrrls: Dazed has an excellent A-Z guide to the women who stomped through the 90s, from Allison Wolfe to zines. Love it. (That’s an expression of my love and a demand for yours.)

Art I’m into right now: Lindsay Bottos offers a clever, artistic response to gendered online harassment. ONOMOllywood, an exhibition from photographers Antoine Tempé and Omar Victor Diop, features iconic film shots re-imagined in Dakar and Abidjan. (It’s sort of an ad campaign for a hotel chain.) The photographs Ibi Ibrahim will soon be showing in the Art14 London Art Fair are a sex-positive response to conservative Islam.

From 6 minutes to 24 hours: Tired of being expected to play a terrorist, Iranian-American actor Jemilah King made a short displaying Hollywood’s narrow view and her much broader abilities. If you’ve got more time, the Global Lives Project curates a collection of films that “faithfully capture 24 continuous hours in the life of individuals from around the world.” It’s a work in progress devoted to cultivating empathy, and there’s a two-week unit for educators to use.

Creativity in places you aren’t looking for it but should be: Women’s World Summit Foundation is seeking nominations for the 2014 Prize for Women’s Creativity in Rural Life, emphasizing sustainable development, household food security, and peace.

expanding the “beloved community”

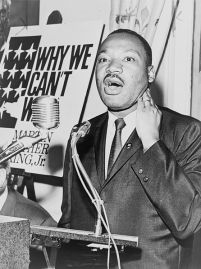

Posted: January 20, 2014 Filed under: art, equality, healing, music, protest, race/ethnicity, violence, visual art | Tags: afros, Beloved Community, Democratic Republic of the Congo, domestic workers, Hutu and Tutsi, Ingoma Nshya, Martin Luther King, Mary Sibande, Mickalene Thomas, New York, rhinestones, Rwanda, Solange, South Africa Leave a comment Today is Martin Luther King, Jr. Day here in the US, so I want to point you to some excellent creative work being done to change power relations in different parts of the world. King was adamant about recognizing how injustices around the world are connected, reminding us that the “destiny of the United States is tied up with the destiny of India and every other nation.”

Today is Martin Luther King, Jr. Day here in the US, so I want to point you to some excellent creative work being done to change power relations in different parts of the world. King was adamant about recognizing how injustices around the world are connected, reminding us that the “destiny of the United States is tied up with the destiny of India and every other nation.”

No matter where you are in the world, decide today to make your work less insular. Find similar groups in other countries, explore art from a different continent, and notice how the same themes resonate. Paying attention to what people are doing on the ground thousands of miles away can change the way you see your community, your work, and the world.

First, reconciliation through music! Drumming is traditionally a male activity in Rwanda, but twenty women, both Hutu and Tutsi, came together to form Ingoma Nshya, a powerful drum ensemble spreading a message of healing. These are women who lived through the Rwandan genocide, and they came to the group with no musical background. Now they play all over the world and have even performed in the war-torn Democratic Republic of the Congo several times.

Next, Mary Sibande is a South African artist working in Johannesburg. Her mixed media installations feature Sophie, Sibande’s alter ego, a domestic worker whose fantasy world reveals the queen inside. In numerous countries, women of color are seen primarily as domestic workers, but Sophie shows us layers and depths that cannot be ignored. Full of life and energy, Sibande’s work demands attention, and Sophie’s shocking blue dress stays with me, as though printed right on the brain. I love them all, but particularly Her Majesty Queen Sophie and I’m a Lady.

Finally, New York-based artist Mickalene Thomas‘s paintings explore female identity and redefine beauty. Her colorful, pulsing work makes me want to dance, and, in fact, she did the cover art for Solange’s EP True. She’s inspired by the kind of women she grew up around, especially her mother, saying, “It’s what I know and what I respect—someone who believes in herself and stands her ground, who doesn’t act according to what society deems as acceptable and expresses herself, her sexuality, her femininity.” Thomas uses the afro to represent that kind of empowered energy and rhinestones to question beauty standards. I love her 2008 album; A Moment’s Pleasure Number 2 and Tamika Sur Une Chaise Longue are standouts.

So whose work are you celebrating today? What other artists, writers, musicians, actors, dancers, crafters, and the like infuse their work with themes of justice, equality, freedom, peace, and love? How are you growing your beloved community?

amplifying quieted voices: elizabeth wright

Posted: December 2, 2013 Filed under: creative process, education, equality, feminisms, healing, music, race/ethnicity | Tags: female musicians, Girls Rock Camp, KnowHow, Knoxville Girls Rock Camp, The Pinklets, Understanding Place Leave a commentI have a guest blogger today! Elizabeth Wright is a social worker, musician, writer, and non-profit consultant based in Knoxville, Tennessee. She is the co-founder of KnowHow and serves on the board of Jobs with Justice of East Tennessee in addition to teaching grant writing at the University of Tennessee. Elizabeth previously served as the executive director of Tennesseans for Fair Taxation and the editor of Knoxville Voice.

Synchronicity is happening with the intersection of feminism and creativity: the same day Sara invited me to write a guest blog post, a reporter from the University of Tennessee’s Daily Beacon student newspaper requested an interview for an article she’s writing on women in music. I also just saw The Pinklets play a show, and was inspired by these three girls under the age of 12 who write their own songs, play their own instruments, and sing songs with lyrics like, “We are entitled to our own opinions” and “You don’t have to tell me I’m beautiful, it’s in my heart and soul.” Feminism, creativity, and discourse are in the air.

I have played music in loud rock bands for 18 years, and while I was comfortable singing on stage hiding behind a bass guitar, it took a long time for me to actually call myself a musician or to feel qualified to speak with authority on the topic. I suspect it’s the same for many women who clearly live with and think about issues related to feminism every day, but it takes a long time for some of us to call ourselves feminists or to feel comfortable speaking with authority about our own thoughts, lives, and experiences. Even if we are moved to speak out, there isn’t always a space where our voices are welcome and heard.

The same is true of anyone whose voice is quieted and who has to fight for equal access and power because of their sexual identity, income level, racial or ethnic background, religious beliefs, ability, or social status. Young people in particular feel the effects of all these forms of oppression and inherit a world that is built around structural inequality, but they often lack access to share their thoughts, experiences, and ideas, contributing to apathy, hopelessness, and disengagement. KnowHow is a new organization I cofounded with a thriving community of feminists, artists, musicians, and social justice advocates to support and empower young people in Knoxville to get involved and to be heard. Our mission is to support leadership development and community engagement among Knoxville’s youth, celebrating art and culture as vital tools to cultivate a deep sense of agency in youth, to amplify their voices as they engage with challenges that affect quality of life for all the city’s diverse residents, and to support them in forming lasting commitments to each other and the world at large.

In working to support youth, we also recognize the importance and necessity of working with and supporting the people, groups, and organizations that work every day to build and improve the healthy communities we all want to live in. One of our goals is to encourage young people to get involved with existing community groups and to facilitate intergenerational leadership that will grow and sustain a local culture of social justice, empowerment, and creative thought and expression.

Toward that goal, KnowHow is co-organizing a free event, “Understanding Place: A Community Dialogue on Race, Geography, and Home” on Saturday, Dec. 7, from 2 p.m. to 5 p.m. at the YWCA Phyllis Wheatley Center (124 S. Cruze Street). The workshop will provide an opportunity for Knoxvillians of all ages to explore how our city’s neighborhoods and communities have been shaped by local history, government policies, and radicalized development processes that continue to impact where we live today, who we count as neighbors, and the places we feel are “home.”

Urban renewal and gentrification have benefited some Knoxvillians over others, but many of us don’t know or understand how our sense of community is shaped by these dynamics. By coming together to learn from community leaders and each other about our neighborhoods and the places we call home, we will start the process of creating a space where diverse voices and experiences are heard, acknowledged and respected, an important building block toward creating healthier and livelier communities. We will also establish and embody a model for how KnowHow seeks to work with and support youth in Knoxville.

KnowHow will follow up with young people at and after the event to support them in researching their own neighborhoods’ histories and collecting and creating personal narratives of their families, neighbors, local business owners, and unsung community heroes and heroines. Their work and creative output will be the source material for a series of workshops throughout 2014, the KnowHow Sessions, which will delve deeper into underlying social issues they uncover and identify, supporting them in examining and sharing their experiences and ideas, and creating visual, performance, audio, and video pieces to share with the community. This work will ultimately create more opportunities for dialogue, education, and the amplification of quieted voices.

In addition to the KnowHow Sessions, KnowHow is also reviving Knoxville Girls Rock Camp in the summer of 2014 in partnership with the Joy of Music School. Rock Camp brings together girls in collaborative music exploration, encouraging them to pick up an instrument, work together, and be loud and proud in expressing themselves.

The music industry is just one aspect of a society that still sexualizes women rather than appreciates our intellect, that silences our voices or belittles our opinions rather than hearing our valid thoughts and experiences, and that denies women access to traditionally male-dominated fields. There is nothing more empowering than reclaiming spaces where our presence is typically denied or ignored and where others have defined our role and level of participation.

By supporting all young people in spaces where change can happen and by amplifying their voices through art, culture, and media, KnowHow seeks to improve quality of life for all the city’s diverse residents and communities. We hope to engage young people in creating the Knoxville we all want to live in together. We’d love to hear your voice, and we welcome your feedback, thoughts, and ideas. Contact us at knoxknowhow@gmail.com.

digging up dead women and rewriting history

Posted: November 4, 2013 Filed under: education, equality, feminisms, gender roles, race/ethnicity | Tags: a room of one's own, American Association of University Women, cemeteries, Cincinnati, Civil War, forgotten women, Frances Wright, graveyards, Nashoba, Shakespeare, Shakespeare's sister, Spring Grove Cemetery, Tennessee, Tennessee Women of Vision and Courage, Tennessee Women Project, virginia woolf, W.B. Scott, women in history 2 Comments I used to write in a graveyard. I went to college in the foothills of the Smoky Mountains, and there was a little Episcopal church in that town with an old cemetery and a small labyrinth made of stones. I’d sit on a bench and write, and when I needed a break or inspiration, I’d walk the labyrinth or wander among the fading tombstones. One day I discovered the grave of the man who had been mayor in 1869. W.B. Scott was the second black mayor in the US, and here he was leading this rural Tennessee town just a few years after the Civil War.

I used to write in a graveyard. I went to college in the foothills of the Smoky Mountains, and there was a little Episcopal church in that town with an old cemetery and a small labyrinth made of stones. I’d sit on a bench and write, and when I needed a break or inspiration, I’d walk the labyrinth or wander among the fading tombstones. One day I discovered the grave of the man who had been mayor in 1869. W.B. Scott was the second black mayor in the US, and here he was leading this rural Tennessee town just a few years after the Civil War.

East Tennessee was mostly pro-Union with all kinds of slavery opponents, but it still surprised me to see that a predominantly white town had a black mayor. The place was clearly proud of this fact all these years later because they’d erected a fancy new tombstone that also mentioned his work as a newspaper editor. I was mighty impressed until I noticed a crooked, faded, half-sunken stone next to it.

Who do you think that grave belonged to?

His wife.

The woman who fed him, sewed and washed his clothes, bore and raised his children, and kept his home clean and his bed warm. The woman who likely listened to his concerns, fears, and ideas; buoyed him when he faltered; and gave him advice and an idea or two of her own.

To leave her grave that sad while her husband’s positively sparkled was a shame. I haven’t been back to that cemetery in years, but I hope they’ve rectified their mistake.

It made me think of Shakespeare’s sister. Virginia Woolf imagined that William Shakespeare had an equally talented sister named Judith. The young woman’s story goes something like this: forbidden to study and married off too young, she ran away, but her inability to get work in the theatre and subsequent impregnation led her to commit suicide. Woolf wrote:

When, however, one reads of a witch being ducked, of a woman possessed by devils, of a wise woman selling herbs, or even of a very remarkable man who had a mother, then I think we are on the track of a lost novelist, a suppressed poet, of some mute and inglorious Jane Austen, some Emily Bronte who dashed her brains out on the moor and mowed about the highways crazed with the torture that her gift had put her to. Indeed, I would venture to guess that Anon, who wrote so many poems without signing them, was often a woman.

The point is that there may have been all kinds of female Shakespeares, Raleighs, DaVincis, Copernicuses, etc., but we never had the chance to meet them because society did not deem it appropriate or beneficial to invest in women’s intellect and creativity.

Not only that, but history is missing women’s voices from all walks of life. History is made up primarily of men’s stories; the whole narrative of Western history is shaped by men, and white Western men at that. Even women who achieved have been written out, erased, forgotten. Women are responsible for the DNA double helix, signal flairs, and computer programming, to name a few, but you wouldn’t know that because men got credit for the hard work of these innovative women.

For the past couple of years, I’ve been fortunate to serve on the advisory council of the Tennessee Women Project. Led by American Association of University Women of Tennessee, this project resulted in a book that highlights women who are missing from Tennessee’s history text books. The book, Tennessee Women of Vision and Courage, just came out, and it includes an essay I wrote on social reformer Fanny Wright.

When I was given the assignment, I knew nothing about Fanny Wright–or many of the other women included in the book. I didn’t grow up in Tennessee, so I didn’t learn state history in school like kids do around here. Over the years, I’ve gleaned bits and pieces, attended history museums, and read essays, but women were often missing from the story. And then I was offered the chance to dig them up and restore them to their rightful places.

The niece of moral philosopher James Mylne, Frances “Fanny” Wright was born in Scotland in 1795, but the promise of egalitarianism led her to the US, where she did decades of work for racial, gender, and economic justice. She created Nashoba, an intentional community outside of Memphis, devoting her attempted utopia to ending slavery and promoting racial integration.

In my research, I discovered that Fanny spent the final years of her life in my hometown of Cincinnati, Ohio. In fact, she’s buried in historic Spring Grove Cemetery, where my grandfather and uncle lie and where I will someday go to visit the graves of my mother and stepfather.

She came all the way from Scotland to Tennessee to work for freedom, and I had to come to Tennessee to find her when she had been in my back yard my whole youth. I’ve worked for women’s empowerment and the elimination of racism for years, and nearly 200 years after Fanny’s arrival, it’s still an uphill battle sometimes here in the great state of Tennessee.

But now I have Fanny’s words to remind me how relatively easy my battle is: “I have wedded the cause of human improvement, staked my fortune on it, my reputation and my life.” True indeed, as you’ll see when you read the essay.

These words are engraved on her tombstone, which, unlike Ms. Scott’s, is prominent and tended. May her memory be as well.

Want to know more about Fanny? Check out the Tennessee Women Project and buy the book from Amazon or CreateSpace.

recent comments