what living is about: low-income kids of color in a white world

Posted: August 18, 2014 Filed under: art, creative process, education, empathy, equality, issues, protest, race/ethnicity, violence | Tags: AmeriCorps, black bodies, black boys, economic justice, Ferguson, Michael Brown, Philadelphia, poverty and creativity, racial justice, shooting of unarmed black boy, volunteering, working with kids Leave a commentFresh out of college, I moved to Philadelphia and joined AmeriCorps. It was easily one of the best things I’ve ever done in my life.

I found myself–a young, middle-class, white woman–walking through the toughest neighborhoods of Philly on my way to improve literacy rates among kids. It was daunting. I imagined all sorts of crazy scenarios, but I quickly learned that no one cared about me. No one was going to bother the white girl in her pickup truck, and the schools all had strict security protocols. Funny where your imagination can take you if you let fear guide it, but recognizing that fear and where it comes from makes all the difference.

Every day for the first couple of months, however, I came home feeling sick. The kids I worked with lived in terrible circumstances, and while I got up close and personal with their daily struggles, I got to walk away from them every day. I got to return to my quaint brick building and eat sundried-tomato hummus from my local co-op.

I wasn’t used to being around extreme poverty, and it made me ache. One of the elementary schools I visited regularly was surrounded on three sides by projects and the fourth side by derelict buildings full of squatters, as evidenced by sheets that hung in random windows. There was a high fence all the way around the building, and inside that fence, at one end, was a small playground that was nothing but blacktop.

One sunny afternoon a boy cried when he learned that it wasn’t his turn to work with me. He had told me the previous week that he watched his mother die of an overdose. He was eight. He was black. He had the sweetest heart you can imagine, but just a few years later you’d probably see him as a thug. Because that’s what happens to black boys. They hit puberty, and we decide they’re dangerous. That may as well be the end of their lives.

At Benjamin Franklin High School, the ninth-grade class I worked with read on a third-grade level, yet they all had passing grades. They weren’t being taught; they were being kept off the streets. There were three pregnant girls. One of the boys who’d done the impregnating strutted around the room while the books provided for them sat in plastic baskets in the back, books about Arthur the aardvark, little boys learning how to play baseball, and monsters eating homework.

When we worked on a project that required us to walk around the neighborhood, drug deals went down right in front of them and they didn’t bat an eye. Maybe they were busy thinking about what Arthur the aardvark might be up to.

Every Monday I spent the afternoon with a group of middle-school and high-school Latinas at a Catholic community center. It was my favorite part of the week despite always needing to go out and move my truck closer to the building before it got dark because a car down the block had been set on fire with a person in it a month before I started. One evening when I went out to move my truck, someone was stealing the car in front of mine. I just pretended I hadn’t seen anything.

The girls were lively and fun and full of ideas, but they were also full of the most heartbreaking stories. One girl told me that her uncle had molested her since she was eleven. I had this idea that two super-smart sisters could do well in school and get out of there, but then I learned that they had no concept of getting out of there. They’d never left their neighborhood. Their mom was an addict who lived and worked on the street, and they lived with their dad and his girlfriend, who was always threatening to kick them out. The older one, in eighth grade, lost her boyfriend when he was shot in the head because he had the best corner.

All of the girls wanted to be Jennifer Lopez, but other than that, they had no thought of moving beyond their neighborhood. It was what they knew. So I tried to nurture their inner JLo. I helped them write about their lives, taught them about acting, and choreographed a dance performance. Every Monday they got a little break from their daily struggle to survive; they got to laugh and sing and dance, which is what living is about.

That was fifteen years ago, and I have no idea what happened to any of those kids. I don’t know who made it, who’s dead, who’s in prison.

I think about them a lot, especially when yet another unarmed black teenager is shot by the police.

I probably didn’t do very much for those kids in the long term, but they did a lot for me. They showed me the reality of poverty and racism. They showed me how the justice system didn’t (and still doesn’t) work in communities of color, how authorities and the media have let down communities of color over and over again. Sometimes I knew about violence that didn’t make the news for some reason. Sometimes it made the news in a way that was utterly different from the story I’d heard from people who were there.

I will never stop fighting for racial and economic justice because I know the lives of kids depend on it. But sometimes it’s difficult to know what to do, especially if you’re white and middle class.

If there are demonstrations in your city, go to them. Connect with the people there to work on real change for the future.

If you work with low-income kids, find ways to nurture their creativity, which can give them solace from the difficulties in their lives and effective ways to work through those difficulties.

If you lead camps or workshops for kids, find ways to make them accessible to low-income kids. Make sure your group is diverse in terms of economic background and race/ethnicity. Get white kids accustomed to diverse environments so they question situations where everyone is white.

If you’ve got some time to volunteer, find an organization or collective that works with kids in low-income areas. Read with kids. Let them sing and dance and paint.

But don’t go in thinking you can save them. They don’t need to be saved, especially by a white person. Think of it as skill sharing or knowledge sharing. You’re going to share what you know with them, and, in turn, you’re going to learn a hell of a lot about the rest of the world.

And then share what you’ve learned with other people. Apply it to your work. Use it to change systems that have long been mired in racism and aren’t doing anyone any good. Use it to increase diversity among decision-makers. Don’t let kids get out of third grade without meeting appropriate reading levels. Question why law enforcement is mostly white in a mostly black city and the effect that has on both police and those being policed. Use strategic creative action.

When I look at pictures of Michael Brown, the young man shot in Ferguson, Missouri, on August 9, I see that eight-year-old boy crying because I don’t have time for him that day. What do you see? Don’t let fear drive your creativity and overrule your empathy. Look beyond the characteristics you have been taught to fear. Imagine that little boy and how different his life could have been.

Here are some other steps white people can take to prevent another Ferguson and work for racial and economic justice.

malala day: give a kid a book already

Posted: July 14, 2014 Filed under: art, education, feminisms, fiction, healing, issues, literature, music, protest, race/ethnicity, violence | Tags: Alice Walker, bikini kill, books, education, girls, kathleen hanna, Malala Day, Malala Yousafzai, mix CDs, mix tapes, Rebel Girl, Sylvia Plath, The Bell Jar, The Color Purple, youth 1 CommentToday is Malala Day, the birthday celebration of Malala Yousafzai, the girl the Taliban shot in the head because she wanted to go to school. That was two years ago, and I am still moved by everything she does. It’s so easy to let life unravel in the face of horrible circumstances, and yet she kept going, keeps going. Her continued existence would have been enough to fight back. Going back to school would have been enough. But Malala skyrocketed, becoming an advocate for girls’ education and a role model for girls all over the world.

Her brave yet peaceful response to the Taliban, and to all who try to hold girls back, is a great lesson for our warmongering leaders, if they took the time to really listen to girls. She doesn’t fight violence with violence; she fights it with education and, more precisely, books. Check out this new video where she explains how books are stronger than bullets.

Malala just turned seventeen. My niece is going on fourteen, and the night before she came to visit us last week my partner and I watched The Punk Singer, the movie about Kathleen Hanna. It got me all fired up about making a mix CD for my niece. (Side note: since the 80s and 90s are back in, will kids start making mix tapes again? Pretty please?) My partner and I started talking about how so much of our values and world views came from the books we found at the library or borrowed from friends, the records we collected from thrift stores and out-of-the way shops, and the zines we traded when we were kids.

My feminist life, for instance, started when I cracked open The Bell Jar and discovered that someone had put my feelings into words. The Color Purple started me on the path to racial and economic justice. When I listened to “Rebel Girl,” Kathleen Hanna was the queen of my world. I devoured these books and records and then I learned about the women behind them, and I finally had an image of the kind of woman I wanted to be.

I wanted to create, to agitate, to express myself. Each book or record was like a window to what could be.

By the end of my niece’s visit, we walked out of a used bookstore, arms piled high with books and CDs. Malala had to face gunmen to get to books; we only had to stroll into a shop the size of a warehouse and take our pick.

Though we in the US are lucky to have access to free public schools, there are a lot of arguments about the state of education here today. Teachers have their hands tied by nonsensical standardized tests that leave children of color further and further behind. To make matters worse, attendance and performance here are affected by everything from street violence and school attacks to dating violence and bullying.

But there is one way we can help young people get at least a little of the education they need. For Malala Day, think about the things that helped you find your way when you were younger, that helped to define who you are today–a book, record, print, poem–and give a copy to a kid.

Books are #strongerthan bullets.

i am over “strong women”

Posted: May 26, 2014 Filed under: art, creative process, equality, feminisms, film, gender roles, protest, television, violence | Tags: #yesallwomen, female characters, Isla Vista shooting, misogyny and violence, strong female characters, strong women, violence against women, women in film, women on television Leave a commentAs I write this, I keep peeking at the #YesAllWomen Twitter conversation, where women are explaining what it’s like to live with the constant threat of male violence thanks to misogynistic attitudes that caused a young man to kill seven people and injure several others at UC Santa Barbara. He was angry that women wouldn’t sleep with him. See, we never know if this guy is lurking inside the dude who harasses us on the street or sidles up to us at the bar, so we say, “I have a boyfriend” and grip our keys between our knuckles.

Recently, on a late-night walk with my partner, I thought we’d walked enough and wanted to go home and sleep, but he wasn’t done. He said he could just meet me at home. I said, “Uh, it’s a forty minute walk back on dark streets where no one walks, and I don’t even have my phone or ID. You think I’m walking that by myself?” He does it all the time, so he didn’t think twice about it. Must be nice, I thought, to not live with the kind of fear women live with for good reason.

This isn’t what I want to talk about this week, but I can’t stop thinking about it. It’s constantly under the surface as I do other things. I’m so relieved that people are having this conversation instead of ignoring the reason this guy plainly gave for his actions and the reason women die at the hands of men every day around the world.

But what I want to talk about isn’t totally unrelated.

My subject today is “strong women.” Please, can we stop saying it? Screenwriters and directors who care about female characters just a little more than the average filmmaker use this term a lot. So do the people who interview them, stunned that someone might see women in complex ways. And so do people who want to see more of these women on screen. It’s become shorthand for fully drawn female characters or female-driven stories. I was going to give you a few examples, but there are just so many and if you haven’t come across this term a hundred times in the last year, then you probably don’t have a TV anyway.

It isn’t that I don’t appreciate the sentiment. I get what these people are saying and appreciate what they are doing.

The problem, however, is that the still fairly new idea of making movies with “strong women” implies that such women are a rarity. That there are loads of women out there who are little weaklings just floating around waiting for a big, strong man to reel them in and protect them from all the harsh difficulties of real life. That most women don’t know how to handle life on their own.

What is the male corollary of the strong woman? In film or fiction, it’s just…a man. No one says, “Gee, I love that this director focuses on strong male characters” because that wouldn’t make sense. Men get to be who they are and women, if they are lucky, get to be strong women. I asked my partner to tell me the first thought that came to him when I said “strong man.” He said, “A man in a striped, old-timey bathing suit with a waxed mustache and a heavy barbell.”

Need I say more?

Honestly, I don’t know any women who aren’t strong. Do you? Every woman I can think of–whether family, friend, colleague, or acquaintance–is strong in her own way. I used to work for a nonprofit that housed women who had faced intimate partner violence, sexual assault, addiction, prison and other problems that totally disrupted their lives. Some of them had worked or lived on the streets. Many had lost their children. Nearly all had faced sexual abuse when they were young. You might assume that these were weak women. That might be what you associate with drugs and domestic violence and prison and sex work. But they were the strongest people I’d ever met in my life. Each one was working to overcome a series of debilitating problems that all began when someone they trusted had hurt them in ways many of us couldn’t imagine. They had reached rock bottom and gotten back up. I’d say that’s as strong as it gets.

You don’t have to kick someone’s ass to be strong.

What we really mean when we say a film or TV show has strong women characters is that we’ve been shown a more comprehensive view of those characters’ lives. Someone has taken the girlfriend of the hero and shown us other parts of her life. We can see that every minute of her life does not revolve around the hero, that she has agency, her own concerns and interests and desires. By showing us other sides of the usual narrative, we can see her as the hero of her own life. This isn’t anything special. It’s every day for more than half the world.

#YesAllWomen

We live with the threat of violence every day. And we go about our business anyway. You think we’re not all strong?

(If you want to read more on this subject, I recommend Mike Adamick’s “We Don’t Need More Strong Girls in Movies” and Sophia McDougall’s “I hate Strong Female Characters.”)

the day we fight back against mass surveillance

Posted: February 10, 2014 Filed under: art, creative process, protest, violence | Tags: digital privacy, mass surveillance, privacy and creativity, right to privacy, Take Back the Tech, The Day We Fight Back 2 CommentsIf you were reading my blog in November, then you know that I coordinated Take Back the Tech!, an international campaign to reclaim ICTs for the prevention of gender-based violence. Our theme was public | private. We encouraged people to see privacy as a fundamental human right, draw their own lines between what is public and what is private, demand privacy, claim public spaces, and connect notions of public and private to gender-based violence.

Fighting mass surveillance was a critical part of Take Back the Tech! How can we expect individuals, employers, and corporations to respect our right to privacy when our own government violates it every day? That’s why I’m participating in The Day We Fight Back, a campaign sponsored by an international coalition of organizations to bring an end to mass surveillance. Join us on February 11 as we fight back against the NSA. Sign up to participate, share the campaign on your social media, blog about privacy, or participate in one of the many events happening in cities around the world.

Privacy is essential for a lot of obvious things, from intimacy to democracy, but it’s also an important part of my creative process. Not everything I write is meant for public consumption. Much of it is trial and error, working through creative and life problems, or a healthy release. Some writers are up for sharing from the get-go, but I’m very private with drafts. I was the same way back in my theatre days. I needed time alone to get comfortable with a scene or song before I’d let anyone see it. I think this is why writing suits me more than being on stage. It’s solitary. I can wander through it as long as I want with no one watching. I like to perform, but I don’t like every moment of working on a performance to be, well, a performance because it’s the process that I enjoy most. It’s the getting there.

That’s what my art is: every moment I’ve put into it from beginning to end, not just what you see when you finally get to look at it. It turns into something else for you, which is fine and as it should be. The process itself lives in my private experience.

I can sit in a packed meeting or buzzing crowd and sneak off into a place inside my mind that no one has ever been, and that kind of privacy is essential to my well-being. It’s where I find peace and it’s where I find ideas. So for me, the right to privacy is as much about the right to explore even when I’m stuck inside as it is about bodily integrity.

The internet has become a key tool for exploration for all of us, hasn’t it? How much do you use the internet for your creative projects? In the past week alone, I used it to find a solution to a knitting problem, inspiration for the bedroom I’m redoing, articles and opinions on a subject for a short story I’m writing, movies that leave me thinking about narrative or character development, recipe ideas for red cabbage, and topics for my blog.

With each click, I left a footprint. Corporations can follow my trail to sell me things; governments can use it to make sure I’m not a terrorist or to do absolutely anything they want. That’s right, anything. You might say, oh, I have nothing to hide. It doesn’t matter. I don’t want anyone inside my head, and following me through my day is pretty damn close to inside my head even if you can never quite get to that place no one else has ever been.

So February 11 is The Day We Fight Back. Let’s make statements, but let’s also think about ways to protect what’s left of our privacy. Take Back the Tech! has several Be Safe strategies for maintaining digital privacy, and we’re working on more. If you have additional ideas, please feel free to leave a comment below. #privacyismyright

for further exploration: music, art, film, and creative solutions

Posted: February 3, 2014 Filed under: art, creative process, education, empathy, equality, feminisms, film, for further exploration, gender roles, music, performance art, protest, race/ethnicity, sexuality, the body, violence, visual art | Tags: Allison Wolfe, Antoine Tempe, art and Islam, creativity in development, creativity in rural life, cultivating empathy, Dakar, Global Lives Project, Ibi Ibrahim, Jemilah King, Lindsay Bottos, Maria Alyokhina, Masha Gessen, Nadezhda Tolokonnikova, Omar Victor Diop, online harassment, ONOMOllywood, Pussy Riot, racial inequality in film, riot grrrl, zines Leave a commentThe latest on Pussy Riot: Formerly imprisoned members Nadezhda Tolokonnikova and Maria Alyokhina are coming to New York to talk about political prisoners for an Amnesty International event. Despite Putin’s attempts to silence them, Tolokonnikova and Alekhina remain unwavering in their commitment to social change. Journalist Masha Gessen’s recently published book Words Will Break Cement: The Passion of Pussy Riot is at the top of my must-read list.

More riot grrrls: Dazed has an excellent A-Z guide to the women who stomped through the 90s, from Allison Wolfe to zines. Love it. (That’s an expression of my love and a demand for yours.)

Art I’m into right now: Lindsay Bottos offers a clever, artistic response to gendered online harassment. ONOMOllywood, an exhibition from photographers Antoine Tempé and Omar Victor Diop, features iconic film shots re-imagined in Dakar and Abidjan. (It’s sort of an ad campaign for a hotel chain.) The photographs Ibi Ibrahim will soon be showing in the Art14 London Art Fair are a sex-positive response to conservative Islam.

From 6 minutes to 24 hours: Tired of being expected to play a terrorist, Iranian-American actor Jemilah King made a short displaying Hollywood’s narrow view and her much broader abilities. If you’ve got more time, the Global Lives Project curates a collection of films that “faithfully capture 24 continuous hours in the life of individuals from around the world.” It’s a work in progress devoted to cultivating empathy, and there’s a two-week unit for educators to use.

Creativity in places you aren’t looking for it but should be: Women’s World Summit Foundation is seeking nominations for the 2014 Prize for Women’s Creativity in Rural Life, emphasizing sustainable development, household food security, and peace.

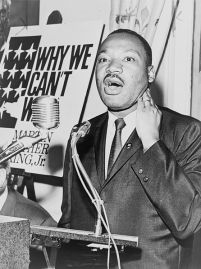

expanding the “beloved community”

Posted: January 20, 2014 Filed under: art, equality, healing, music, protest, race/ethnicity, violence, visual art | Tags: afros, Beloved Community, Democratic Republic of the Congo, domestic workers, Hutu and Tutsi, Ingoma Nshya, Martin Luther King, Mary Sibande, Mickalene Thomas, New York, rhinestones, Rwanda, Solange, South Africa Leave a comment Today is Martin Luther King, Jr. Day here in the US, so I want to point you to some excellent creative work being done to change power relations in different parts of the world. King was adamant about recognizing how injustices around the world are connected, reminding us that the “destiny of the United States is tied up with the destiny of India and every other nation.”

Today is Martin Luther King, Jr. Day here in the US, so I want to point you to some excellent creative work being done to change power relations in different parts of the world. King was adamant about recognizing how injustices around the world are connected, reminding us that the “destiny of the United States is tied up with the destiny of India and every other nation.”

No matter where you are in the world, decide today to make your work less insular. Find similar groups in other countries, explore art from a different continent, and notice how the same themes resonate. Paying attention to what people are doing on the ground thousands of miles away can change the way you see your community, your work, and the world.

First, reconciliation through music! Drumming is traditionally a male activity in Rwanda, but twenty women, both Hutu and Tutsi, came together to form Ingoma Nshya, a powerful drum ensemble spreading a message of healing. These are women who lived through the Rwandan genocide, and they came to the group with no musical background. Now they play all over the world and have even performed in the war-torn Democratic Republic of the Congo several times.

Next, Mary Sibande is a South African artist working in Johannesburg. Her mixed media installations feature Sophie, Sibande’s alter ego, a domestic worker whose fantasy world reveals the queen inside. In numerous countries, women of color are seen primarily as domestic workers, but Sophie shows us layers and depths that cannot be ignored. Full of life and energy, Sibande’s work demands attention, and Sophie’s shocking blue dress stays with me, as though printed right on the brain. I love them all, but particularly Her Majesty Queen Sophie and I’m a Lady.

Finally, New York-based artist Mickalene Thomas‘s paintings explore female identity and redefine beauty. Her colorful, pulsing work makes me want to dance, and, in fact, she did the cover art for Solange’s EP True. She’s inspired by the kind of women she grew up around, especially her mother, saying, “It’s what I know and what I respect—someone who believes in herself and stands her ground, who doesn’t act according to what society deems as acceptable and expresses herself, her sexuality, her femininity.” Thomas uses the afro to represent that kind of empowered energy and rhinestones to question beauty standards. I love her 2008 album; A Moment’s Pleasure Number 2 and Tamika Sur Une Chaise Longue are standouts.

So whose work are you celebrating today? What other artists, writers, musicians, actors, dancers, crafters, and the like infuse their work with themes of justice, equality, freedom, peace, and love? How are you growing your beloved community?

poverty and creativity

Posted: December 23, 2013 Filed under: art, creative process, empathy, ethics, healing, protest | Tags: creativity out of poverty, creativity out of struggle, madness and creativity, poverty and creativity Leave a commentA fellow poet and friend once said to me, “For the sake of your writing, I hope you’re as miserable as I am.” This was a few years after college, and, thankfully, I had matured enough not to feel the need to spend late nights holed up in my room, smoking cigarettes and scribbling as though it would save my life. (Though writing did, and still does, contribute to my sanity.)

Indeed, when I was younger, my creative thrust seemed to come from life’s trials, which led me to glamorize the tumultuous and desperately sad lives of writers like Dylan Thomas, Sylvia Plath, and Jack Kerouac. I accepted the popular image of the writer’s life–a constant zigzag of madness, inspiration, misery, success, loneliness, and celebration. All the bad things were simply the price of creativity.

Then I grew up and realized I didn’t actually like wallowing in despair. I stared down some pretty tough things I hadn’t expected to happen and found that I only wanted to get through them and move on. And in my work and my travels, I saw a kind of poverty and despair far worse than anything I’d ever experienced, which is something I remind myself of from time to time. I’m not living in a war zone. I’m not starving. I’ve got warmth and love and organic tomatoes fresh from the garden (well, not at the moment since it’s winter, but I’ve got holly cut from the trees in the back yard). Things aren’t that bad.

Over time, I learned to write when I was happy and when I was bored and when I was just whatever. I realized I didn’t need to use writing like a drug; it could be a normal part of my life, like buying groceries or taking a shower. And still something really wonderful could come out of it.

Two weeks ago I wrote about my apartment block in Poland, which was a concrete box. What I didn’t tell you is that it was one of the nicer places to live. What I didn’t tell you is that my pay as an ESL teacher, though certainly not much in US dollars, was higher than the average Polish salary. So while I felt a bit trapped in concrete painted in soothing pastels, I didn’t mention that my life was pretty comfortable despite the lack of aesthetic.

And that got me thinking about how much creativity comes out of poverty, how if you look at the lives of people who are struggling to make ends meet, you’ll see some pretty inventive ways to get by. But how is the need to be creative different from the luxury to be creative?

I said in that post that I’ve always needed creativity. But that’s more of a mental thing than a physical thing. As I said above and have said in other posts, it has been a part of my survival strategy, but that’s about my mental health, not about trying to put food on the table or keep a roof over my head. I did spend most of my twenties living in relative poverty, however, so I know how “making do” makes you a special kind of artist. I made do for so long that I was well into reasonable comfort before I realized I could just replace the things in my house that I’d rigged to keep working.

So what’s the difference between creative solutions to one’s own poverty and masterpieces created in prosperity?

Much of the art we cherish most has come from times of struggle, but we have to refrain from glamorizing that struggle. I think we need to recognize creativity as a necessary part of life but also think about what fear does to creativity. Sometimes fear sharpens it and sometimes it erases it.

I think we need to emphasize the important role creativity can play in helping people overcome struggle. But we also need to remember that creativity doesn’t require pain. Creativity can come out of poverty, but it can also come out of pleasure. And, more importantly, it can come from somewhere in between.

On any average day. The sky’s a little cloudy, but the weather isn’t too cool. The neighbor’s dog is barking at the recycling truck. I had some work to do today, but I’ve got the rest of the day off. I’ll mop the floors later and do a load of laundry. I’m thinking about lunch, but instead of the kitchen, I head to my desk. I don’t have anything particular to say, but I’ll start writing and see what comes out.

I do this even when I don’t need to figure anything out or make a statement or feel some specific kind of release. I do it because it’s part of my day. It’s a normal part of life.

As we delve into winter and the holiday season, it’s important to remember what poverty means for so many people in the world. I think about people whose lives are full of fear instead of good things and how that affects their inner world as well as their outer world. We all need self-expression even when we are our own audience.

Even when profound art comes out of struggle, we shouldn’t let that justify poverty and pain. I’ve had good things come out of horrible experiences, but I’d still choose to keep the horrible experiences from happening in the first place. Instead, we should imagine what that artist could have achieved with everything they needed, learn the lesson they are sharing, and resolve to make things better for the next generation. Because my average day would be a blessing for many.

tv women: olivia pope, mindy lahiri, and emily thorne

Posted: November 18, 2013 Filed under: education, empathy, fiction, for further exploration, protest, the body | Tags: Adam Pally, Agnieszka Holland, Anders Holm, bisexual characters, Emily Thorne, Emily VanCamp, Gabriel Mann, Happy Endings, Hillary Clinton, Judy Smith, Kerry Washington, Lena Dunham, Lisa Kudrow, Madeleine Stowe, Mindy Kaling, Mindy Lahiri, Olivia Pope, Revenge, Scandal, sexist media, Shonda Rhimes, Tavi Gevinson, The Mindy Project, The Office, womanist, women directors, women on television, women writers, Workaholics Leave a commentDo you watch television? I’m sure many of you don’t, and I get that. We don’t have cable because we’re not interested in being sucked into TV all the time, but we do watch some. We catch the big cable shows later on Netflix or DVD, and I watch a few network shows in addition to PBS. I often like to follow a good story and compelling characters while I’m knitting a scarf or folding my laundry or painting shutters (which we have too many of), so I don’t care so much about whether the medium is film or TV. Plus, television is a great place for women these days, far better than film.

I’m not going to pretend that these shows are ideal. Or that even their feminism is ideal. But I appreciate the changes I’ve noticed in television the past couple of years, especially the increased focus on narratives of women of color. It’s not just women actors who are benefitting from these changes. I’m also noticing more women writers and directors. Yes, women directed some of your favorite episodes of Breaking Bad and Mad Men. One of my favorites is Agnieszka Holland, who directed episodes of The Wire, Treme, and The Killing. Then there’s Deadwood, the filthy, brilliant western, with an unusually high number of shows written by women. Even if the popular cable epics aren’t strong on complex women characters–where’s our female Walter White, Don Draper, or Tony Soprano?–women are increasingly making decisions behind the scenes.

Here are a few of the shows I’m watching because they feature fantastic women characters, especially women of color, and they’re entertaining.

If you watch TV, how have you not become one of Olivia’s gladiators? It’s such a relief to see a strong black woman as the center of a show. Olivia Pope is a game changer for women in TV, a sharp, sophisticated political genius who fixes every problem Washington, D.C. throws at her. Her team will do anything for her, and men keep risking their careers to be with her. I tire of Olivia’s star-crossed love with Fitz (aka, Mr. President) because it occasionally turns her into a wobbly pool of jello, but all the other scenes make up for it. Plus, Olivia Pope, the fixer, is based on a real black woman, Judy Smith, America’s #1 Crisis Management Expert.

Have I told you how much I love Kerry Washington? She proudly identifies as a feminist and womanist, actively engages in politics, and talks wisely about important issues in interviews. And this season’s addition of Lisa Kudrow as Fitz’s opponent in the upcoming election is divine. As Congressperson Josie Marcus, Kudrow recently got to deliver a whopping, off-the-cuff feminist speech that shames the sexism of her opponents and the media so deliciously that it must be right out of Hillary Clinton’s fantasy world. It doesn’t hurt that the show was created by Shonda Rhimes, herself a black woman who happens to be one of the most successful show runners in the business.

Mindy Kaling didn’t just play Kelly Kapoor on The Office; she was also one of the writers and directors. Then she published Is Everyone Hanging Out Without Me? (And Other Concerns). And then she created The Mindy Project: she produces, directs, writes, and stars in this sitcom about Mindy Lahiri, a successful OB/GYN trying to figure it all out in New York. She’s the very first South Asian-American woman to have her own show. Her character is confident about her work, loves her body, and says what she thinks. And she’s Hindu. And she’s sex-positive.

Kaling and the show have had to deal with some backlash, and there have been some weird moments. But I’m holding on because there are many more smart moments and her character is really new and fresh. The show’s heavy on the cameos, but some of the best episodes involve Anders Holm, of Workaholics, as Mindy’s boyfriend. The two have great chemistry, and their tent scene in “Take Me With You” of Season 1 had me giggling for days. The Mindy Project also rescued Adam Pally, whom I’d been missing since Happy Endings was canceled.

Additionally, I love how Kaling has been calling out the sexist, racist, and image-obsessed media lately. She’s tired of being asked about her weight and her ethnicity instead of her work. If you need more of a reason to like her, check out Lena Dunham’s interview with Kaling for Tavi Gevinson‘s Yearbook 2.

This show is a total guilty pleasure. My sister and I text each other in the midst of it: “Did she really do that?” “But how is he alive?” “Noooooooo!” Like Scandal‘s over-the-top plot lines, Revenge is designed to be somewhat absurd. That’s what makes it fun, especially when Emily Thorne (Emily VanCamp) comes face to face with her nemesis, Victoria Grayson (Madeleine Stowe, who is active in women’s rights, by the way).

Emily is secretly destroying virtually every evil rich person in the Hamptons, and I love it when the girl next door kicks ass (see Buffy the Vampire Slayer). Now, I don’t normally like revenge stories because I think revenge is a useless concept, but this is basically an evening soap opera. And we frequently see the downside of vengeance with deaths and broken friendships. Emily comes complete with ninja skills, a mentor who trained her at a revenge school(!) in Japan, a British revenge companion, and an endless supply of complicated emotions.

One of the best parts of this show, however, is Nolan, Amanda’s closest friend, confidante, and partner in crime, played by Gabriel Mann. A tech genius and hacker, Nolan is equally sweet and sly, and he’s bisexual. Those around him treat his sexuality as completely normal, not batting an eye when he goes from pining over Padma to falling hard for Patrick. Yes, television, you can have characters with diverse sexualities and not make their stories all about said sexualities.

So what would you add to this list? Or remove?

for further exploration: los muxes, street harassment, and frieze

Posted: October 21, 2013 Filed under: feminisms, for further exploration, gender roles, protest, race/ethnicity, sexuality, the body, violence, visual art | Tags: African artists, David Cross, Frieze, Hannah Price, London, los muxes, Mexico, New York, Nicola Okin Frioli, Nil Yalter, Oaxaca, Philadelphia, street harassment, Tatyana Fazlalizadeh Leave a commentIt’s that time where we take a look at a few things we should learn more about, so let’s have at it.

I am obsessed with this collection of photographs from Nicola Ókin Frioli. Los muxes, gay men in the Mexican town of Juchitán, are beloved by the community. Families consider them a blessing, a good luck charm. They drink, work, and legislate in traditional Oaxacan dress: flower-embroidered blouses, brightly colored skirts, and scarves wound through long hair. Yet another reason I should figure out how to retire to Oaxaca.

When the subject of street harassment comes up, people usually argue about how best to deal with it. I’ve tried ignoring it, yelling back, giving the finger, and looking straight at them to ask why they think it’s okay to talk to women that way. David Cross has a hilarious joke about what these men might be thinking when they holler at us, but what I really want to direct you to are two women’s artistic responses to street harassment. In City of Brotherly Love, Hannah Price photographed Philadelphia men just after they harassed her. She captures an interesting moment; some guys look uncomfortable with the lens on them, while others don’t seem to care. Likewise, Tatyana Fazlalizadeh captioned her drawings of women with the things she wanted to tell harassers and then hung the posters around Brooklyn. They sparked a community conversation as people scribbled their thoughts in the blank spots.

Finally, Frieze Week–with two major art fairs and countless gallery openings–just happened in London, and it highlighted more African artists than the city had ever seen. Included as a Frieze Master was feminist artist Nil Yalter. Yalter’s photographs, drawings, paintings, and installations typically focus on aspects of the lives of women and immigrants.

recent comments